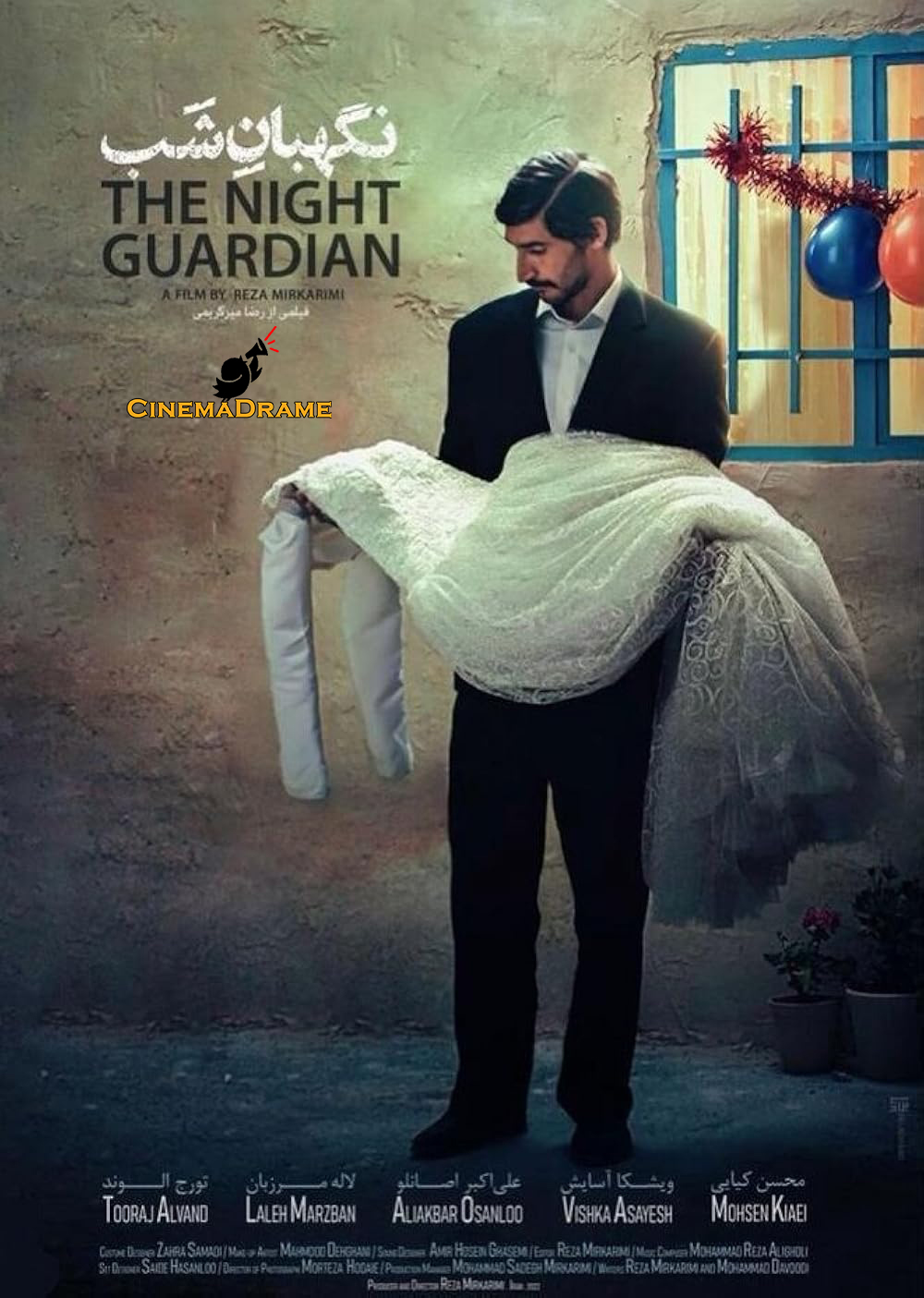

Loghman Madayen’s Critique of The Night Guardian: A Film That Aims to Teach How to Say No!

According to cinemadrame News Agency, Loghman Madayen, a film critic, penned an exclusive note on Reza Mirkarimi’s film The Night Guardian, writing: We find this profound work by Reza Mirkarimi characterized by a calm narrative, realistic portrayal, and a psychological approach. It speaks from the heartfelt pain of educators and incorporates the dilemma of military service alongside land drought and the unemployment of farmers. It takes a psychological look at the dark past of those involved in economic corruption, examining verbal violence within families to identify the root of problems. It lifts the veil on propaganda driven by greed and aims to revive the courage to say “no” in society, so that those who feign social justice cannot achieve their desires by buying votes and exploiting the masses. Thus, it can be said that it has beautifully conveyed the essence of its content.

The initial minutes are well-crafted: the audience quickly grasps key parameters of the characters Behnam and Rasoul, and very soon, they are captivated and engaged by the humorous dialogues and the commendable performances of both characters.

The main plot revolves around a laborer named Rasoul, who, with the drying up of his agricultural land, comes to the city hoping to find work. Finding a job coincides with starting a family for him, but Rasoul has a significant weakness: the inability to say “no.” The film has no shortage of good subplots, from the uncle’s forgetfulness and his story with his son, to the tale of Nasibe’s marriage and her sister’s difficult life, or Behnam’s bitter past. The screenplay is so detailed that it even delves into the former building guardian, which is considered a strong point.

Rasoul is an “anti-value” at the beginning of the film: he trusts easily and pays a heavy price; he is unable to say “no” and constantly falls victim to others. But in the end, he learns to stand firm against what he doesn’t believe in and say a strong “no,” at which point he transforms into a “value.”

The film suffers from an extremely weak hero and antagonist. There is no challenging obstacle in his path to compel him to strive, and on the other side, we have an antagonist who, with every setback, also tries to remedy it. This means that instead of the hero, it is the antagonist who is removing his obstacles. Another weakness of the screenplay is the resolution delivered by the writer, where, surprisingly, all of Rasoul’s affairs resolve themselves automatically, from his marriage and home ownership and release from prison to the sale of the dry lands he said were worthless.

The film has few moments of suspense. Nothing surprises the audience until the climax of the film. The character of the engineer bombards the audience with so much information that everything becomes predictable. We only witness effective suspense in two parts: first, when the police officer arrives with an arrest warrant, and then when it is revealed that Behnam has been chatting with Rasoul’s wife the entire time, and he breaks.

The planting, development, and payoff in the screenplay are very precise and excellent. Everything effective in the film is seen at least three times, such as when Rasoul plants flowers around a tree with a burnt trunk to repair it, and then tells his uncle that his father told him that if we don’t respect the tree, it will get angry and dry up. There, the uncle is affected, and later we realize he was the gardener of this land and would visit every night to water the trees, and he gets angry with his son for not watering the trees. Or the engineer who easily speaks of cutting down trees. Or when Rasoul puts his finger on his ballot paper, and a little later, puts the same finger in prison ink to be released. Or where he doesn’t touch the ten-thousand-toman banknote from the educators because he considers it a betrayal of the engineer, and in the end, doesn’t take the engineer’s check because he considers it a betrayal of the educators.

The connecting element is the mobile phone: the same phone the uncle gives to Rasoul, where he hears his deceased son’s voice on the voicemail, to tell us that Rasoul is meant to take his son’s place. The same phone Rasoul’s family uses to communicate with Nasibe, and Behnam uses to chat with Nasibe.

The first inciting incident is where Rasoul receives a permanent job offer, so the challenge begins, and weak obstacles appear in his way. The climax of the film is when the police officer arrives at the construction site looking for Rasoul; there, the truths are revealed, and he realizes that the entire idol he built of the engineer was mistaken, and he defrauded people using his name. The second turning point is when Rasoul doesn’t take the engineer’s two-hundred-million-toman check and instead sells his lands to take his wife to an independent home, and here the story finds peace.

In dialogue, on one hand, we see the revelation of information, which is a weakness, and on the other, we witness a masterpiece in characterization. The dialogues benefit from being simple and fluid, having their own specific idioms and expressions, reflecting customs, traditions, accent, and tone, infused with humor, short and concise, avoiding unnecessary words, and creating conflict.

We observe a strong mise-en-scène that completes the film’s puzzle. The costumes are consistent with each character’s cultural class and social background. Color psychology is incorporated into them, which is excellent. We find Rasoul in a baseball jacket that, apart from its white sleeves, has a red color, symbolizing love and life and indicating his emotional nature, while its white color testifies to his innocence, peacefulness, and purity, which is perfectly exemplified. Rasoul is released from prison at the end, wearing black clothes, speaking of his maturity in trusting others, the secret of his imprisonment that he holds in his heart, and the sorrowful blow he suffered from Behnam chatting with his wife. We see the uncle in a brown jacket, which indicates his flexibility and also his loneliness and isolation—the same flexibility that chose Rasoul as a son-in-law without any preconditions, and the sorrow of isolation he carries from his son’s pain. We see Nasibe in a red coat, which speaks of her passion in love and her eagerness for married life, and we find this intelligence in the production design with its color palettes as well.

In découpage, we witnessed a very good music selection, but there were many extra scenes, and the editing could have been better arranged to maintain the film’s rhythm. The makeup was well done, the necessary light and sound on set were precise, and the camera angles were excellent. For example, when Rasoul first enters the workplace and, with a terrified look, sees the engineer and his colleague behind him looking at the tower model, from his frightened gaze, we guess what has been secretly prepared for him. Or when he gets on the lift and quickly ascends the floors, we realize his rapid growth.

Despite all these points, although there was a serious weakness in refining the screenplay, the actors’ delivery was fully supervised, and each one performed excellently, all shining at a high level with mastery over speech, tone, and dialect, along with avoiding physical contraction and stiffness in speech and personalizing their roles. They were soulful and meaningful and did not fall into typical portrayals.

The character psychology is based on Rollo May’s theory. The story’s hero follows the stages of self-awareness in character development—the very dialogue of the uncle who tells Rasoul, “You must see if you have the courage to say no or not?” Thus, our hero, with an innocence that merely delves into himself and is unaware of the outside world, reaches the stage of rebellion. This is where the educators gather in front of the building, and Rasoul gets slapped by the former guardian to better understand the engineer and make him concerned about the educators and awaken him somewhat from his heedlessness. A little later, he reaches normal self-awareness; now he himself is a victim and embarks on a meaningful and important journey—the same journey Behnam told everyone he was in Bandar Abbas, but he was in prison. After reaching this stage, he finds himself, and finally, upon reaching creative self-awareness, he understands that whoever treats him kindly is not necessarily from God, and he does not accept the engineer’s check and says “no,” and by relying on himself, he reaches manifestation.